In Today’s China, Paradoxes Still Abound. But So Do Opportunities — Site Selection Magazine

–

–

In September, China First Capital Chairman and CEO Peter Fuhrman, familiar to attendees at the World Forum for FDI in Shanghai last year, delivered a talk from China to Harvard Business School alumni. Here, with Mr. Fuhrman’s permission, we present excerpts from his remarks.

————–

–

GDP growth has never and will never absolutely correlate with investment returns.

Any questions? No? Great. Thanks for your time.

Of course I’m joking. But that key reality of successful investing is all too often overlooked, and China has provided all of us over these last 30-some-odd years with a vivid reminder that IRR and GDP are by no means the same animal.

China is, was and will likely long remain a phenomenal economy. The growth that’s taken place here since I first set foot in China in 1981 has been something almost beyond human reckoning. Since I first came to China as a postgrad in 1981, per-capita GDP (PPP) has risen 43X, from $352 to $15,417. China achieved so much more than anyone dare hope, a billion people lifted out of poverty, freed to pursue their dreams, to make and spend a bundle.

China this year will add about $1 trillion of new GDP. Just to put that in context, $1 trillion is not a lot less than the entire GDP of Russia. So who is making all this newly minted money? And how can any of us hope to get a piece of it? Another question: Why, if China is such a great economy, has it proved such a disaster area for so many of the world’s largest, most sophisticated global institutional investors, private equity firms and Fortune 500s?

Turning Inward

Let’s start with the fact that China is a part of the World Trade Organization, but not entirely of it — not fully subscribed in any way to the notion that reciprocity, openness, free trade, level playing fields and equal treatment are positive ends unto themselves. As China has gotten richer it has seen even less and less need to attract foreign capital and foreign investment. That’s a tendency we see in other countries, including obviously some of the rhetoric we now hear in the U.S. — that more of the gains of the national economy should belong to its citizens. But China’s way is different.

The renminbi is a closed non-tradable currency, so getting US dollars into and out of China has always been difficult. China now has the world’s second-largest stock and bond markets, but those markets are largely closed to any investors other than Chinese domestic ones. But China also continues to provide companies going public with by far the highest multiples anywhere in the world.

When I first came to China 36 years ago China was a 100-percent state-owned economy. Twenty years ago the first rules were put in place to allow a private sector to function. Today, according to anyone’s best estimate, it’s about 70 percent private and 30 percent state, and most of the value creation is being provided by that private-sector economy. So in theory there should be very interesting M&A opportunities. But it’s been exceedingly difficult to get successful transactions done. One of the core reasons is that by and large all private-sector companies in China, large and small, are family-owned.

The other thing important to consider is a Mandarin term: guifan. It’s the Chinese way of explaining the extent to which a company in China is abiding by all the rules of the road — the taxes you should pay, the environmental and labor laws you should follow. It’s not at all uncommon that successful private-sector companies in China are successful by virtue of having negotiated to pay little or no corporate tax on profits.

For foreign-owned companies in China it’s an entirely different story. They are by and large 100-percent compliant with the written rules. This has an enormous impact on the operating performance of any company, so you can imagine how potentially skewed the competitive environment becomes. And keep in mind that corporate taxation in China in the aggregate is, if not the highest in the developed world, then among the highest, and the environmental and labor laws are every bit as difficult, rigorous, tough and expensive to implement as they are in the U.S.

China is a country where local government officials are scored on the measurable success of their time in office, and success is overwhelmingly attributed to GDP growth. So it should be no surprise if what they’re trying to do is optimize GDP growth, the percentage of a company’s income that goes back to the government in taxation can have an adverse effect on that. Instead the government will continue to urge its local companies to take the money and, rather than pay tax, continue to invest, expand and therefore build local GDP.

The Hum of Consumerism

The reasons to stay engaged and find a viable investment angle include GDP growth. China’s GDP is likely to continue to grow by at least 6 percent a year. Second, across my 25 years of involvement in China, every one of the predictions of imminent collapse — financial catastrophe, local government debt, bad bank loans, real estate bubbles — have proved to be false. It appears China has some resiliency, and it’s certainly the case that the government has the tools and financial resources to ride out most challenges.

Third has been how effortlessly it’s made the transition that still bedevils lots of Europe, from a smokestack economy to a consumer-spending paradise. At this moment every major consumer market in China is booming both online and offline. Alibaba, Baidu and Tencent are now operating as three of the most profitable companies in the world.

How does China have a robust, booming consumer economy and an enormous appetite for luxury brands, yet on average salary levels that are still one-fifth or one-sixth the levels in the US? The simple answer is that almost all the Chinese now living in urban China — about half the population, compared to about 15 percent when I first got here — owns at least a single apartment if not multiple, which is more and more common. The single best-performing asset in history has probably been Chinese urban real estate over the last 30 years. It’s fair to say the average appreciation over the last 10 years is at least 300 percent.

Though China has a population whose incomes on paper look like those of people flipping burgers at McDonald’s, they seem to have the spending power and love of luxury goods like the people summering in East Hampton. Even Apple itself has no idea how big its market is here in China. It’s likely that at least 100 million iPhone 8s will be sold to Chinese over the next year. The retail price here in China is at least 30 to 40 percent higher than in the US, with most phones bought for cash, without a carrier subsidy.

‘You’ll Be Older Too’

So where is it possible to make money in China? One message above all: Active investing beats passive investing every time. What you need to do is either be the owner-operator or be a close strategic partner with one, and stay actively engaged.

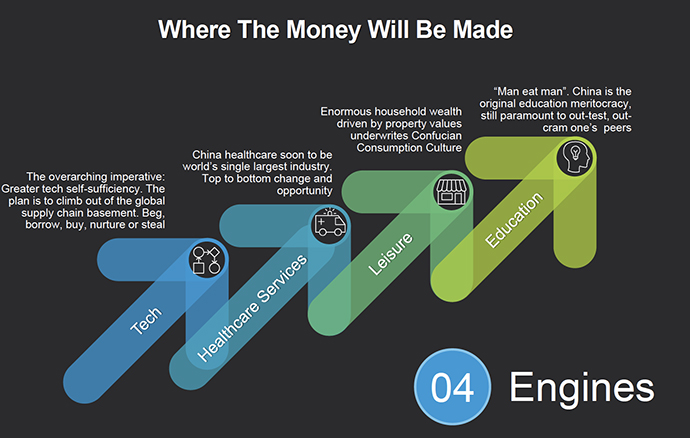

There are four major areas of opportunity: Tech, health-care services, leisure and education (see graphic below). The potential for building out a chronic care business in China is enormous. Looking ahead 25 to 30 years, sadly China will likely suffer a demographic disaster. This country will become a very old society very quickly. That’s the inevitable product of 30 years of a one-child-per-family policy. By 2040 or 2050, 25 percent of China will be over the age of 65.

The overall rate of GDP growth is unlikely to ever rival that of a few years ago at 10 to 12 percent a year, but overall what we have is higher-quality growth. People in China are living well. Things should continue to motor along very smoothly at least for one more generation — a generation whose members are better educated, more skilled, ambitious and globalized than their parents.

There’s no denying the reality of what a better, happier, freer, richer country China has become since I first set foot here. I marvel every day at the China that I now live in, even while I occasionally curse some of the unwanted byproducts like heavy pollution in most parts of the country, overcrowding at tourist attractions, bad traffic, and a pushy culture that’s lost touch with some of China’s ancient glories.

China will continue to amaze, inspire and stupefy the world. The Chinese have done very well and will do better. At the same time, those of us investing in China may do a little better in years to come than we have up to now. More of the newly minted trillions in China just may end up sticking to our palms.

–